Klicke hier für die deutsche Version.

After 5 kilometres of walking I have already seen almost all the promenade in Calais – including its new citizens, the refugees.

If you haven’t seen an refugee for longer than a minute it means you are no longer in Calais.

It’s around 2pm now. My shoulders are aching from carrying my backpack. My arm feels like it’s about 6ft longer from pulling my suitcase along. And I am sweating all over. The holidaymakers and locals still look at me sceptically. I don’t like it at all. At one of the roundabouts, I see a team of journalists lean out of their car and take photos of the refugees as if it’s some sort of Safari. The refugees try to cover their faces quickly.

It makes me think of a way to avoid the stares of the passers-by. I take my camera out of my bag and screw on the wide-angle lens. How quickly a technical gadget can change a role. My new identity works. An old Frenchman gives me directions to a Hostel close by.

What refugee walks through Calais with a digital-reflex camera?

In the foyer, I have a conversation with the porter about the situation of the refugees and why they are not allowed into the Hostels. My room is nearly ready. I just want to shower and rest a bit more.

Whilst I stand at reception allowing my eyes to drift over the carpet, a pair of hipster shoes and hipster trousers enter the hotel. A few seconds later they arrive next to me and a black bag containing a tripod is set down on the floor. I dig the human belonging to the vision. The foot belongs to Volkan Duman from Amsterdam. Volkan is Dutch with Turkish migration background, studies something to do with film and wants to make a kind of documentary about the Camp. That’s great. Whilst I have a chat with this extremely friendly guy, his companion enters the foyer. He does look funny. Long and gangly with a blonde ponytail, he introduces himself as Jasper. Jasper is probably 6ft 7”. And totally cool.

I ask them both whether we should go to Camp together. We shake hands on it. I can help translate their interviews and we can share taxi costs, too. A classic win-win situation, I should say. But the two of them want to leave immediately. That’s heavy. I am totally beat. But I am, to be honest, just as excited to get to know the Camp that people call the Jungle. I quickly take my stuff up to my room and return to Jasper and Volkan with just my camera.

The Jungle, just like the Hostel, is situated directly by the sea. We have to just get around the harbour somehow and then we’re there. At least that’s what it looks like on the map. In reality it’s about 8 kilometres away.

On route, we keep bumping into small groups of refugees. All of them have the same destination: England. Via train through the Eurotunnel. They tell us that we can get a bus for part of the way to the Camp. Which we do. On the way, it turns out that Jasper and Volkan are globe trotters. Volkan is only 24. They met as volunteers working in Zimbabwe. I always have respect for people who travel around the world.

Jasper is growing on me. He stops constantly on route to have conversations with the refugees. Almost all of them he offers a cigarette. Jasper talks to Eritreans, Ethiopians and Sudanese. He somehow radiates when he offers all those broken spirits a little attention and respect. The refugees react positively towards him, we laugh and joke before we part company.

When we study a map on the bus, I find out that where I met Anwar is at one end of Calais and the Camp is directly at the other end. Still 2 kilometres to go. There is one last industrial road that ends in an underpass at the far end. Behind that, the Jungle begins.

Welcome to the Jungle

The closer we get to the underpass, the shorter the distance between the individual groups of refugees. It takes 3 hours to get to the tunnel. On foot, naturally. And 3 hours back. 99% of refugees don’t get further than Anwar and myself, earlier on. Shortly before the tunnel they get stopped by police on the motorway. The officers then tell the refugees in a cacophony of different ways how shit they believe them to be before sending them back to Camp. The impact of this encounter is clearly visible on the faces of those returning.

The Jungle has been growing here since 2012. It’s situated on the Western part of the harbour, next to the motorway to the ferry. The sunsets here are wonderful. If there weren’t the barbed wire fence you could almost say it was romantic.

When I reach the front entrance of the Camp, I am met with a sea breeze. It contains various scents. In the next few days it transpires that it doesn’t just smell of burnt plastic, open fires and oriental cooking. It also smells of frustration, anger and despair.

You would only recognise those smells if you had spent time in a slum. Because that is exactly what people call the Jungle. In my opinion, it is a community which consists of 5 separate slums. An Afghan, a Pakistani, an Iranian, a Sudanese and an East African slum, and by the latter I mean the Habashi Quarter with its Eritreans and Ethiopians.

We decide not to carry our cameras around with us openly but to somehow mask them with our clothing. We do this out of respect for the refugees. We don’t want them to feel like animals in a Zoo where visitors have never seen such exotic species.

Walking past various shops and food outlets, we come across some boys from Pakistan playing cricket. Just behind them there is a group of twenty boys in the Afghan quarters playing volleyball. Everywhere there is the indigenous music of that particular community. There is a constant rush of refugees riding past on bicycles as if they had to quickly get to work somewhere. And who would employ these poor devils. It’s prohibited.

This ban is making people inventive. They have their own shops. One is a hair dresser, another knows how to quickly build a hut. Another is running a shisha bar. There is even a hut with a pool table. You can play pool there for a Euro an hour, with snacks and drinks.

My little brother would probably find that awesome. He would probably find a way to somehow take part in these extraordinary happenings. But the humans who are living here and who want to be somewhere else probably don’t find it at all comforting.

The Jungle of Calais is a bit like a festival terrain.

Only without any of the fun.

Having walked halfway through the Camp I realise that there are almost no women. I have to think of the neo-Nazis who tried to imply the refugees were cowardly and egotistical because they send the men first. So I begin to ask around for the reason of the absence of female refugees.

They are telling me about a former Youth Hostel in which the women and children are housed. The Salam. That’s where the food is distributed from as well. This area is only accessible to the refugees. It is right next to the Jungle. Which lies right next to the Atlantic coast in the most beautiful sand dunes in the North of France.

I soon form my own impression of Salam. Around 1500 men and young lads stand to queue in front of the huge iron gates of the old Youth Hostel. When helpers open the gates, it often comes to scenes that are less than pleasant. Everyone wants to be first when food gets handed out. Nobody wants to wait for two hours to have a shower until the others are finished before them. There is also tension by the electric points where you can charge your mobile phone once a day. To observe this is uncomfortable. I had hoped I could start my report with something funny or interesting.

The plastic church

We go back to find the Church. I can’t wait to finally see it. It’s supposed to be in the Habashi area behind the Afghan quarters. We come across some stand pipes. There is a hosepipe buried in the ground. It feeds all around the Camp. Sometimes when the pipe sticks out of the ground it almost looks like a normal tap on top of a metal pipe. This is where the inhabitants of the Jungle get their water not only for cooking but also for washing themselves and their clothes. Most of them wash themselves and everything else right there and then. That’s exactly what it looks like, too. For the first time, we have to wade with our beautiful European clothing through the mud and slimy water mixed with shampoo and washing powder.

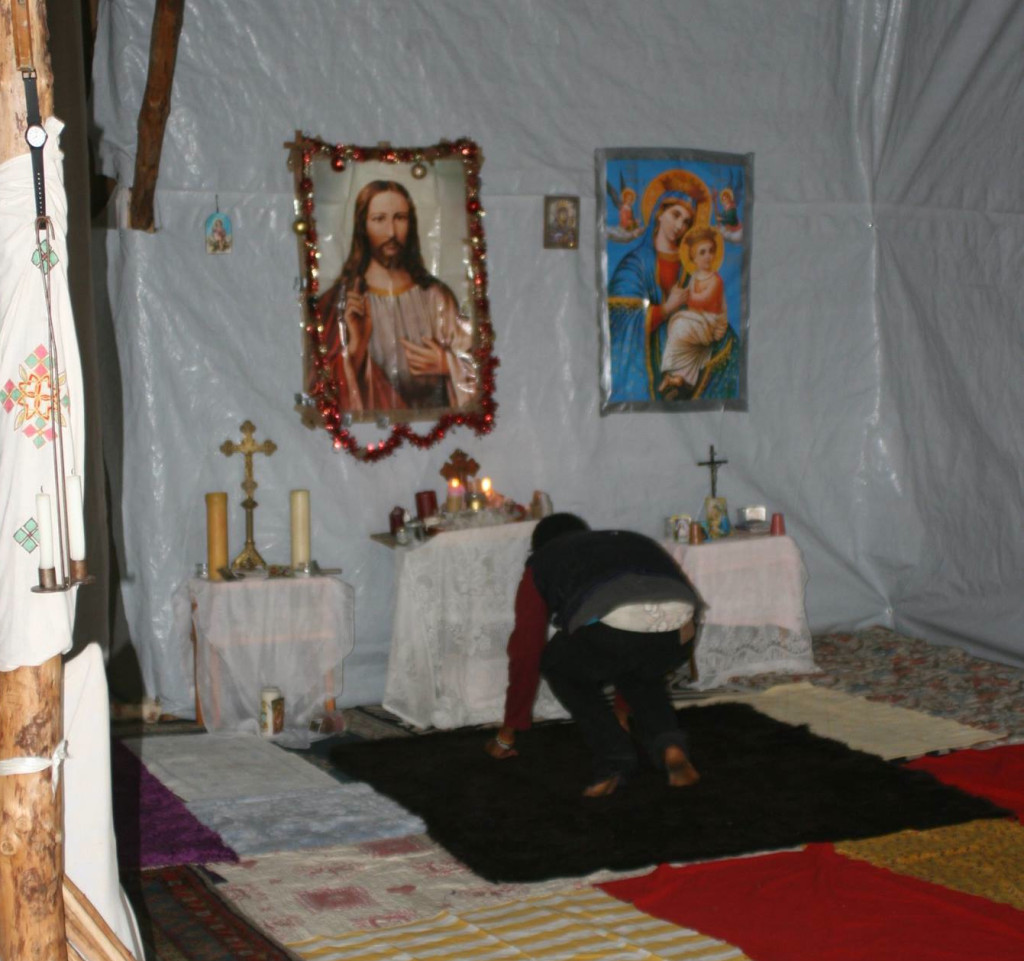

Past the stand pipes we then reach the Habashi quarters. The Habashi are a tribal group from Eritrea and Ethiopia. Many amongst them are Christian. The Habashi are very passionate and emotional about their religion. They have built this incredible Church in their quarters. The plastic Church. It consists of this wooden structure covered in white sheets of plastic. The cross above the entrance is raised some 40ft above the ground. In front of the Church there is even a bell which they use to call people to prayer. After asking three or four times, I meet the man who I am introduced to as the one who is in charge.

His name is Eli. Probably named Elias. But I don’t want to pry because I have heard that people live here who have been persecuted in their own homelands.

Eli is 34 and Eritrean. He tells me everything about the Church. He is very friendly and forthcoming. I am, however, not allowed to take a photo of him. Not yet. I reach out with my hand and ask him about the Camp and the Church. It is unbelievably beautiful to find out so much fascinating information here, bit by bit, and be told so many things. Eli is getting more relaxed with me. He doesn’t seem to be trying to put me off any more. In the conversation, I ask him if he thinks that Jesus might have had dark skin. He laughs and then says

It doesn’t matter what Jesus looked like.

It only matters that he existed. (Eli)

Eli is now my friend. I am very proud of that fact. The other refugees are always quite short with me and are limiting their contact to the absolute necessary. Probably because of our cameras. I begin to feel like I am going to learn something incredibly amazing here. That’s how I always feel when I travel and get to know people who you usually only see on television. These people don’t just look like they are on telly. They are the people who really are on TV.

People like Eli have very modest wishes. And they are always honest. In my world these qualities are priceless. So I ask Eli what I could bring back with me as a gift for him or his community on my next visit from Germany. He answers that he wishes to never hear news of my return because he hopes to be long gone by then, preferably by tomorrow. I don’t know how to react to this bitter truth. Thankfully, Jasper is near. He takes Eli by the arm and asks him to show us the Church from the inside. Lucky refugee.

By the entrance, Eli makes the sign of the cross and takes off his shoes. Inside the Church, he explains what the Church is all about. You can see that there is pretty much everything in there that you would find in any other average Church, albeit in limited form. They have holy water, an altar, prayer books in various languages, images of deities and wooden sculptures of Jesus and Mary, even kneeling benches for the elderly. I am impressed.

But one thing impresses me even more. It’s so quiet here. In the middle of the Jungle. It’s a great experience. I would love to lie down on the carpets of the Church and sleep for a while. And most likely nobody would mind. But Jasper has already opened another conversation outside with a new refugee. And so the three of us try to tease a little information out of him. The place that they built in order to reach God becomes the space for us to connect with other humans.

Click here for Day 3: True Friends and Freeloader

Click here for Day 5: I am not Animal

Photos: Hammed Khamis | Translation by Ulrike Muller